Our playbook for investing in commodities has historically been to identify high-quality assets that sit at attractive points on their commodity cost curve, and to establish a position when the balance sheet is solid and the commodity price has cost curve support (i.e. some producers are losing money at spot pricing). Management also matters in mining: poor management plus windfall commodity prices are a recipe for the chequebooks-out-at-the-top dynamic that has sadly been a feature of most commodity cycles. Further, good managers and good company cultures render it easier to attract talent in competitive markets. This combination of factors is pretty rare, we have only made a handful of such investments since the fund’s inception, including:

- BHP: We have held a position in BHP since the fund’s inception, which we added to meaningfully as the stock fell below $40.

- MinRes: We invested in Mineral Resources in 2018 when it was bringing online a quality asset in Wodgina at a time when lithium was on the nose. When we first invested, MinRes was a net cash business (how times have changed). We exited our position in 2024 as the balance sheet had deteriorated.

- IGO: Exiting MinRes on balance sheet concerns, we purchased IGO, which had a net cash balance sheet and owns a quarter of the highest-quality hard rock lithium asset in the world, Greenbushes in WA.

- Santos: We held Santos for a number of years, exiting the position this year when the Adnoc bid emerged. The stock has subsequently fallen from $8 to $6 as the bid fell over and oil prices have languished around US$60/bbl. We have since re-entered the stock.

Of course, there have been many missed opportunities along the way as various commodities and their ASX-listed exposures have rallied. However, broadly we have found it very lucrative to remain disciplined and only add commodity businesses when these four preconditions are met: quality assets, good balance sheet, commodity out of favour, and solid management.

We have added a new position in the fund this quarter that we believe meets these criteria, adding Rio Tinto as new CEO Simon Trott outlined a credible path to a simpler, higher-value business at its Capital Markets Day. The outlook includes significant cost-out, asset sales and production growth in key commodities of iron ore, copper and lithium to drive value to 2030. Rio has quality, tier 1 assets in its key commodities, net debt to ebitda <1x, and exposure to commodities with attractive supply/demand dynamics. This is in addition to our core portfolio holding in BHP.

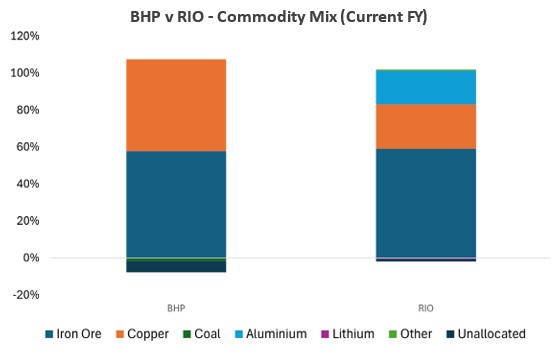

While both BHP and RIO have had a solid year of returns, up 25% and 14% respectively, they have lagged pure-play peers; for example, ASX-listed pure-play copper exposures Sandfire Resources and Capstone Copper are up 53% and 87%, respectively. This is despite the significant copper exposure of both companies, with 40% of BHP’s current earnings from copper, and 20% for RIO. It is also worth noting that out to 2030, BHP’s production mix will hold relatively stable, while RIO’s incrementally shifts towards copper as Oyu Tolgoi ramps up.

Source: Company data, Airlie Research

We believe the valuation opportunity for both diversified miners comes as the market is unwilling to “pay up” for the 50-60% of both businesses that currently comes from iron ore. This is largely because of the future supply coming from the Chinese/Rio-owned Simandou project in Guinea, considered to be a “Pilbara-killer”.

However, there are a few reasons why we believe iron ore prices may stay resilient in the face of new capacity. Firstly, we note the operational complexity of Simandou, which may make operating at nameplate difficult. The project relies on a 650-kilometre railway corridor that runs through varied topography and crosses multiple river systems. The rock formations at Simandou exhibit characteristics that create instability in open-pit walls, thus posing technical challenges that require specialised stabilisation techniques and specialised workforces, which may be hard to come by in remote Guinea, and in the middle of a broader resources rally that draws on a limited pool of such workers. Simandou ramp is already disappointing, with Rio’s maiden 2026 guidance of 5-10mt sales sitting 30% below consensus expectations.

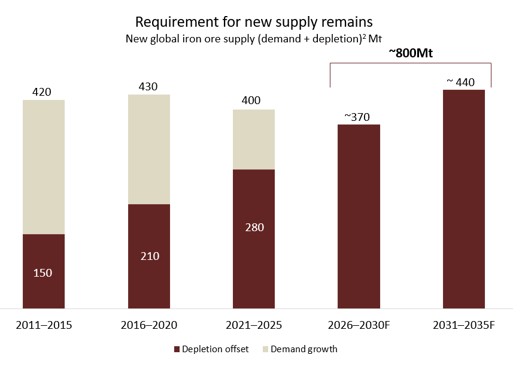

Second, “good” ore is getting harder to maintain at scale. This is reflected in Rio’s recent move to lower the Fe content of its flagship Pilbara Blend Fines. The effect of this is twofold: as grades drift, mills will need to either pay a higher price for higher-grade units or consume more tonnes of Fe per tonne of steel, both paths are supportive of resilience in the benchmark price. Further, ageing tenements will drive the need for further investment to replace ore depletion. The chart below from the Rio investor day highlights the size of the issue, forecasting 370mt of additional supply needed over the next four years simply to replace what is depleted (i.e. assuming flat demand). Even if Simandou were to ramp perfectly and on time, we would be looking at an incremental 120mt (albeit very high-grade ore) by 2029. This increase may not be enough to close the gap.

Source: Rio Tinto

Thirdly, declining iron ore prices are the consensus expectation, and this is creating the valuation opportunity. Medium-term consensus forecasts for iron ore are in backwardation over the next four years, falling to US$80/t (62% Fe, FOB). Rio and BHP trade on forward price to earnings multiples of c13-14x, with consensus below spot for both iron ore and copper. At spot commodity prices, the FCF yields for BHP and RIO are 6% and 9%, respectively. If we run long term real prices of US$80/t for iron ore and US$4.60/lb for copper, we get 5-13% upside for BHP/RIO. While this doesn’t sound too compelling, for the reasons articulated above we believe the iron ore market may in fact anchor around prices higher than US$80/t over the medium term, with periods of supply tightness causing periodic price spikes that generate free cash windfalls in excess of the above valuation base case.

Further, from a portfolio construction perspective, it is worth noting that BHP (to which we are overweight) is trading at almost a record low price to book relative to CBA (to which we are underweight).

Source: Airlie Funds Management

All that glitters? Airlie views on the gold price and ASX gold sector

It is also worth touching on the part of the resources sector that has had the strongest performance over 2025: the gold sector. We do not currently own any gold stocks in the portfolio, and this has been costly for us this year, as the gold sector has doubled as a proportion of the ASX 200. We have historically treated gold in the same manner as any other commodity investment, seeking opportunities that meet our four criteria: quality assets at attractive positions on the cost curve, solid management, strong balance sheet, and a commodity price with cost curve support. That latter criterion is a shorthand for the “valuation” part of our investment process- our thinking is that commodities where some producers aren’t making money at the current spot price is a sign that the commodity may be out of favour, a hunting ground for equities that may be mispriced.

It is this valuation criterion that was not met by the ASX gold sector- all miners, no matter how marginal, should be making money hand-over-fist at current gold prices. However, a deep dive on the gold sector has led us to the conclusion that we were wrong in applying that criterion of cost-curve support to the gold sector. It has unique qualities such that waiting for cost curve support is the wrong signal- in fact that may lead you to purchase gold equities early into a long bear market. However, these unique qualities make forecasting price very difficult, and we step through them below.

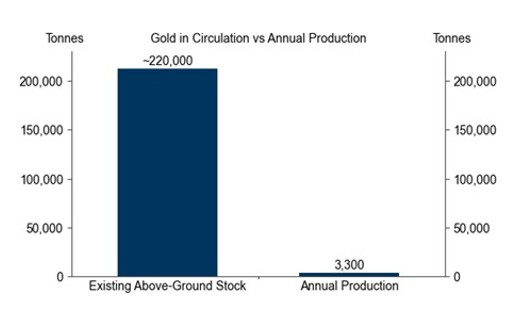

There is an argument that gold should not be thought of as a commodity, but rather as a currency, or store of value. Gold doesn’t get used, it simply changes hands, and in doing so it is repriced. Unlike normal commodity businesses, where high prices cure high prices by incentivising more supply, the gold price can’t be punctured by a wave of supply. (That’s what makes gold, gold). As the below chart shows, nearly all gold that has been mined still exists, and its stock dwarfs the sum of annual production, which adds just 1% to the total supply each year.

End-2024-data

Source: USGS, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

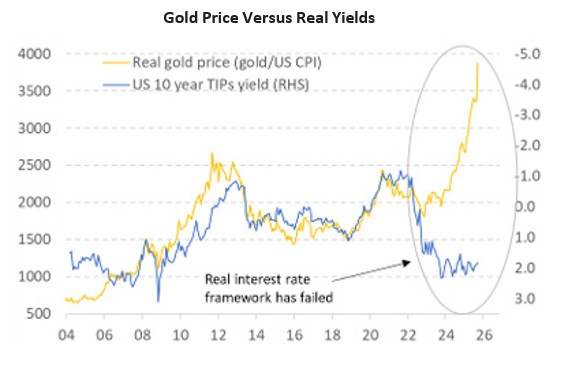

This makes forecasting the gold price very difficult. One can turn to normal historic correlations to predict conditions in which the gold price might “work”; however, these historical correlations are now breaking down. Gold typically moves inversely with real yields (i.e. nominal yields less inflation). This is because gold is a non-yielding asset- when real yields rise, investors can earn a higher inflation-adjusted return in safe bonds, which raises the opportunity cost of holding gold. As per the below chart, this historic correlation has not held over the past three years; as real interest rates have risen, so too has the gold price

Source: MST Marquee

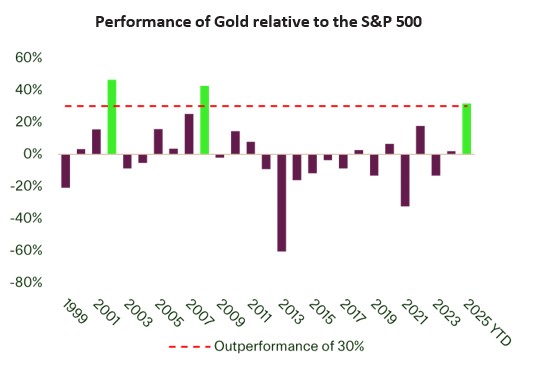

The gold price also typically performs strongly in years when equities falter – see below. The only years prior to this when gold outperformed equities to this degree were during the deep market drawdowns of 2001/02 and 2008. Gold has outperformed equities by over 30% this year, despite the S&P 500 posting a strong return of nearly 18%.

Source: MST Marquee

So what’s going on with the gold price? In our view, a combination of central bank purchasing and persistent fiscal deficits is driving the strength. The G7 decision to freeze cUS$300bn of Russian assets following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine has created a deep distrust of the USD for many central banks. China, India and others have increased their purchasing of gold to reduce their reliance on the US dollar, likely fearing similar sanctions against their reserves. As difficult as it was to forsee this dynamic (it certainly caught the US off guard), so too is it difficult to predict the degree of marginal demand for gold in the future. In this sense, gold is unlike other commodities, and more like a collective idea.

Meanwhile, gold miners remain imperfect vehicles through which to express a positive view on a gold price at all-time highs. While we are only guessing what the gold price may do, we have a higher degree of certainty as to what miner cost bases will do (rise as they draw on the same limited pool of skilled workers and grades fall), and what production may do versus expectations (disappoint!). Gold mining is tough- gold deposits have high short-range variability, which means you can hit a great patch and then nothing a few metres away. This makes it difficult to build an accurate resource model and design a mine plan that delivers steady head grades. Grade variability and orebody complexity drive frequent production guidance misses. This is fundamentally the reason why gold is a fantastic store of value- it’s production can’t be easily toggled up to meet the signal of higher prices.

So if the key driver of gold equities (the gold price) is something that is very difficult to predict, and if gold miners tend to cost overruns and production misses, does that render gold equities uninvestible to us? The answer is no, but it makes us cautious. In many ways, the above dynamics sound like the perfect set up for ever-rising prices: inelastic demand from price-insensitive central banks, a structural geopolitical overlay, supply that simply cannot respond to higher prices in a way that spoils the party. However, this dynamic works in reverse as well. In a normal commodity cycle, prices fall to a point where a portion of higher-cost producers aren’t making money- they eventually reach a point where they can’t sustain losses and mines close, sewing the seeds of an eventual price recovery. In this way, the responsiveness of supply to pricing acts as a handbrake on price at the top, and a cushion to price at the bottom. This cushion doesn’t exist for gold producers, and for this reason, bull and bear markets in gold equities tend to last many years, on average.

There seem to be two noisy ideological camps with respect to gold investing: those who refuse to invest in gold because of the difficulty of predicting the gold price (famously typified by Warren Buffett), and ‘gold bugs’ who think every portfolio should have a significant portion allocated to gold (e.g. Ray Dalio). We do not ascribe to either camp, and remain open-minded. We are keeping a close eye on the sector as these historic correlations between the gold price, equities and interest rates break down. Uncharted territory in investing typically drives volatility, and the challenges of gold mining will definitely drive volatility for mining equities- we expect opportunities may emerge in sharp sell-offs.

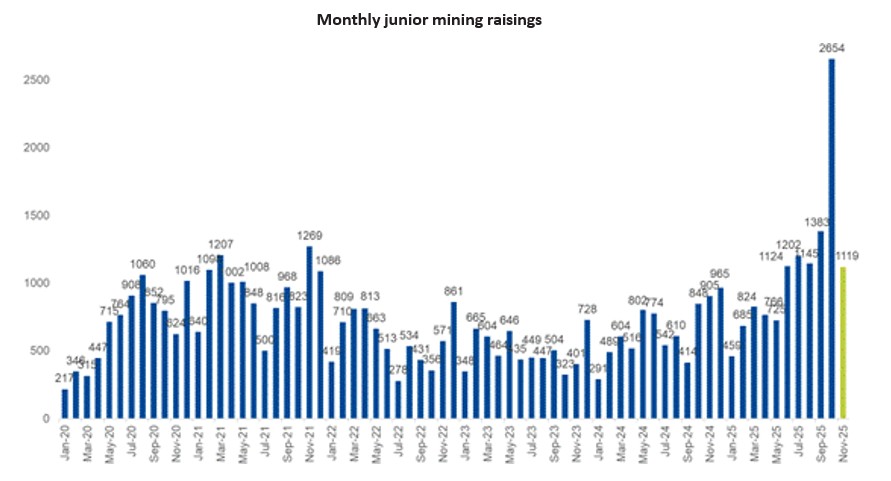

To date, the portfolio has had second-order exposure to a rising gold price via our investment this year in ALS Limited, a global lab-testing company. ALS’s Commodities business, which comprises roughly half its earnings, has a market leading Geochemistry business with strong market share and excellent returns on capital (c30% through the cycle). 75% of ALS’ Commodities revenue comes from testing services directly linked to exploration spend. Global exploration spend is dominated by gold and copper miners, who account for 70% of total spend. We believe the recent strength in gold and copper prices puts the Commodities business on the cusp of a material earnings upcycle, driven by an acceleration in capital raised by junior miners (as shown below).

Source: Morgans, Factset

This is beginning to show up in ALS’ testing volumes. During exploration upcycles, there is very little capital investment required for ALS to handle additional volume. These periods are also accompanied by pricing power, all of which can lead to significant incremental margin on sales, and returns on capital that approach 40%. In our view, this business provides exposure to higher gold (and copper) prices without the accompanied cost base inflation that gold miners experience during such periods.

Emma Fisher

Deputy Head of Australian Equities